In a rainforest that Sumatra cradles, its native elephant turns to the indigenous rhino and asks it to toss a coin. “Heads, you live. Tails, you vanish.”

As this coin flipped skyward, many more betting on the lives of wild species in today’s world are being tossed — with fate deciding whether the animal can outlive all challenges in the world through swift adaptations, or decline rapidly towards extinction.

Extinction and evolution are often seen as polar opposites. One representing death, the other life. Yet, in the grand theatre of natural history, they have always been two sides of the same coin. Species have evolved, thrived, while some of them have completely vanished. Life moves on. The Earth has survived five mass extinctions, where entire species were lost, giving way to new ones that played the survival game and lived on. Extinction, in this sense, is not a villain, but a process that takes place due to natural causes.

But the extinction we witness today is different. It is no longer driven solely by evolution instilled by nature. It is being shaped by deforestation, pollution, climate change, and the slow violence of indifference. For the first time, a single species known as homosapiens is the dominant force behind the disappearance of species. Simultaneously, scientists are inching closer to resurrecting extinct animals through cutting-edge technologies. We find ourselves on the cusp of an unsettling question: even if we can bring species back from the dead… should we?

What is Extinction?

Extinction is the permanent “dying out or extermination of a species”; the moment when the last known individual of a population dies, and no living successors remain. Crudely put, it is nature’s full stop, closing a chapter of evolutionary history that will never be written again.

In Earth’s long timeline, extinction is neither rare nor unnatural. It is part of the cycle that shapes biodiversity itself. Scientists refer to this slow yet continuous process as background extinction, which occurs due to environmental shifts, competition, or natural selection. When extinction rates spike dramatically and wipe out vast swathes of life across ecosystems, we call it a mass extinction. Ecologists have alarmed us that one to five species are becoming extinct each year, which is thousands of times faster than the normative rate of background extinction. This is happening largely due to loss of habitat, relentless hunting, human induced climate change, and other anthropogenic activities. At this rate of extinction, we are bound to lose as many as 30-50% of species by the middle of this century.

Mass extinctions press nature’s reset button, and have been historically followed by bursts of new life. They have helped clear ecological space for new forms to thrive and evolve. But what distinguishes these from today’s rapid rate of extinction is the dominance of human ambition and activity, not nature’s intent.

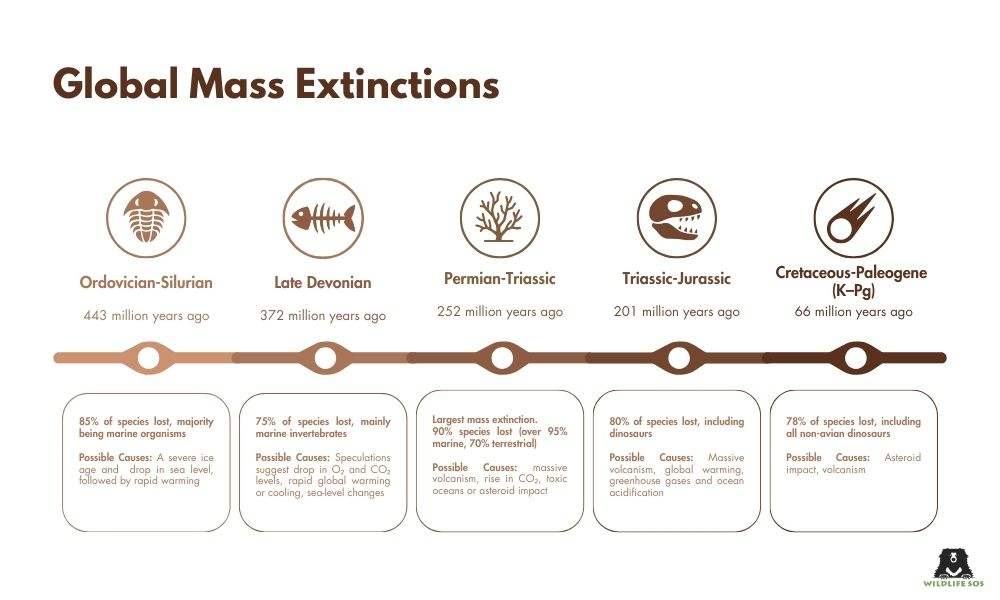

The Past 5 Mass Extinctions

Over the past 540 million years, Earth has witnessed five major mass extinction events, each of which eliminated at least 75% of all species in a geologically short span of time.

Are We Living Through the 6th Mass Extinction

Scientists call our current time the Anthropocene, a geological age indelibly shaped by human hands. Through pollution, overfishing and the relentless clearing of forests, we may be teetering on the brink of a sixth mass extinction, unless we are already within its grasp.

Unlike the previous five mass extinctions which unfolded over hundreds of thousands or even millions of years, the present crisis is unfolding at a rate that is 35 times faster as per research studies. And this time, no asteroid or volcanic eruption is to blame.

A landmark UN report from the Intergovernmental Science‑Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) warned that over one million plant and animal species face extinction, and may be lost in the coming decades due to pressures including:

- Devastation of more than 50% of tropical forests through deforestation

- Climate change disrupting habitats and food chains

- Pollution, generating over 400 million tonnes of hazardous waste annually

- Invasive species introduced through trade and travel

- Over‑exploitation via hunting, fishing and wildlife trafficking

Remarkable Yet Extinct Species

Before we explore the possibilities of reversing extinction, it is important to remember those we have already lost. Here are some species that have vanished largely due to human-driven activities:

- Pinta Island Tortoise

Chelonoidis abingdonii | Ecuador

With his long neck and expressive eyes, Lonesome George, a subspecies of Galápagos giant tortoise, was one of the rarest reptiles on Earth and became a global symbol of conservation. Discovered in 1971 on Pinta Island in the Galápagos, he was believed to be the last of its kind. The tortoise population had already been decimated in the 19th and early 20th centuries by whalers and settlers who hunted them for food and also introduced goats that ravaged their habitat. Scientists and conservationists tried to find George a mate, even introducing closely related females in hopes of breeding a hybrid, but all efforts failed.

- Western Black Rhinoceros

Diceros bicornis longipes | Africa

Declared extinct by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) in 2011, the western black rhino had once roamed Cameroon, Southwest Chad, and surrounding regions. Its horn, falsely believed to cure ailments or bring status, became its death sentence. Rampant poaching — even in protected zones — wiped out the small, scattered populations that remained.

Despite being declared a protected species in the 1930s, enforcement of anti-poaching laws was inadequate. Conservationists attempted to monitor and secure remaining individuals through aerial surveys and patrols, but corruption, lack of funding, and civil unrest rendered many efforts fruitless. No verified sighting has occurred since 2006.

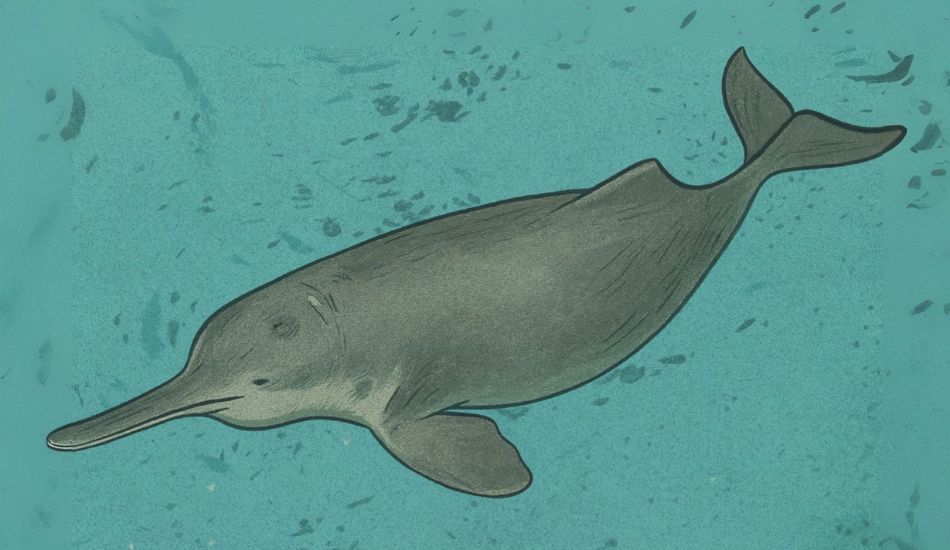

- Baiji River Dolphin

Lipotes vexillifer | China

Once gliding through the Yangtze River, the baiji was known in folklore as the “Goddess of the Yangtze”. As China’s industrialisation surged, so did the baiji’s decline. River damming (notably the Three Gorges Dam), illegal fishing with electricity, heavy boat traffic, and water pollution devastated its habitat.

In 2006, a six-week expedition by international scientists failed to find even one baiji, making the Chinese river dolphin officially being declared as extinct. It was the first dolphin species and the first cetacean species to disappear due to direct human activity.

- Splendid Poison Frog

Oophaga speciosa | Panama

Vivid in colour, tiny in size, and once vibrant in Panama’s tropical rainforests, the splendid poison frog vanished by 2020. Scientists believe the species was particularly vulnerable to the amphibian chytrid fungus, a disease causing fungus which began sweeping through the region in 1996 — just a few years after the frog’s last recorded sighting in 1992.

The frog’s habitat was also under threat from deforestation. Efforts to breed similar poison frogs in captivity have seen success, but Oophaga speciosa was lost before it could be saved. Another cause of the frog’s extinction was for them to be poached and traded as pets.

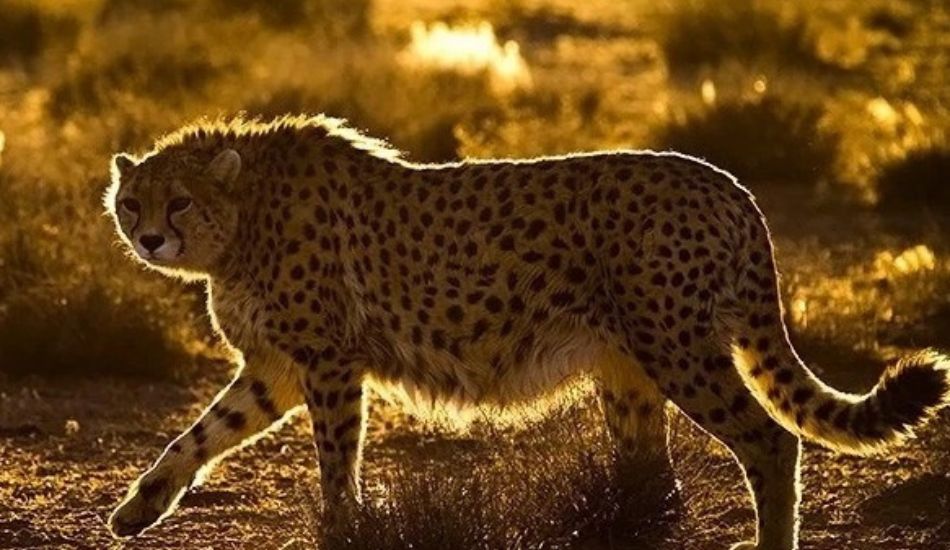

- India’s Asiatic Cheetah

Acinonyx jubatus venaticus | India

The Asiatic cheetah once roamed India’s grasslands, celebrated by Mughal emperors for its speed and elegance. But it was relentlessly hunted for sport, and its prey base was destroyed by expanding agriculture. By 1952, it was officially declared extinct in India, and a small population of it can only be found in Iran, where it is currently listed as Critically Endangered by IUCN.

With high ambition, India recently launched an ambitious Project Cheetah in 2022, reintroducing African cheetahs into Madhya Pradesh. The reintroduced animals are, however, genetically distinct from India’s original subspecies.

De-extinction

Once the stuff of science fiction, ‘de-extinction’ has now stepped into the real world of scientific realm. Its goal is to bring back species that no longer walk this Earth, using biotechnology to recreate, reengineer, or resurrect them.

Three main methods for de-extinction are being explored:

- Cloning, using preserved DNA to create a genetic duplicate — though famously fragile. The first cloned extinct animal, the Pyrenean ibex, died minutes after birth.

- Selective breeding, where scientists amplify traits of extinct species still found in their living relatives — like efforts to recreate the aurochs, an extinct species of bovine.

- Genome editing, a technology used to splice extinct genes into the DNA of modern relatives. A leading biotechnology and genetic engineering company is working to revive the woolly mammoth by altering the genome of the Asian elephant. Similar efforts are underway for the thylacine, passenger pigeon, and even the dodo.

Yet, no species has been truly restored to the wild. At best, we have blueprints and beginnings. At worst, we have a spectacle without substance. This raises the question: Are we reviving life, or merely simulating it?

A Distraction from the Living?

De-extinction may seem redemptive — a second chance for species we failed to protect. But just because we can, doesn’t always mean we should. Most species disappeared because their habitats vanished. Bringing them back without restoring those ecosystems is like releasing someone into the ruins of a home long burned down.

There’s the obvious risk of disruption. Ecosystems today are fragile, already under pressure from invasive species introduced to lands that are not native to it, climate change and depletion due to encroachment. Reintroducing long-lost animals could cause chaos rather than healing. Many cloned or engineered animals suffer deformities, high mortality, and compromised health — which makes us both responsible and accountable for their welfare. Are we prepared to bring life back, only for it to suffer?

Perhaps the most insidious danger is the illusion of reversibility. If extinction can be undone in a lab, are we showing less urgency about protecting what still survives? Morally, de-extinction raises deeper questions — who are we bringing these creatures back for? Why are we not channeling our efforts and funds instead to safeguard those that are threatened or critically endangered?

There’s a world of difference between a wild creature shaped by millennia of evolution and a lab-born organism patched together from fragments of DNA. One is born into a forest. The other comes to life in a lab. And there’s something unjust in reviving the dead while the living slip through our fingers. Mammoths may return in headlines, but will that stop the suffering of elephants today? Why try to recreate extinct frogs while living species perish from pollution and disease?

At Wildlife SOS, we work to protect the life still breathing beside us. Rescuing animals from cruelty, restoring habitats, treating the injured, and standing with communities to create a future where wildlife can thrive. De-extinction might work one day. But until we learn to appreciate and work towards conserving the living species, reviving the extinct will remain a distraction from what our co-inhabitants desperately need. To know more about the fascinating world of wildlife and conservation, you can subscribe to the Wildlife SOS newsletter today.

Feature image: Canva