One of India’s most recognisable and keystone wildlife species, the Asian elephant (Elephas maximus), has made a quiet but noteworthy comeback to the forests and villages of Chhattisgarh, after being declared locally extinct in the 1920s. Elephants had begun to reclaim these lands once again in the 80s, and studies suggested that this was when their habitats in the neighbouring states of Jharkhand and Odisha were lost to massive deforestation activities.

- Elephants gradually migrated back into Chhattisgarh, carving out new paths through forests and farmlands in search of space, safety, and sustenance. [Photo © Chhattisgarh Forest Department]

It was in the year 2009 that elephants were first recorded in the divisions of Balodabazar and Mahasamund in the state. While this marked a hopeful return for a once locally declared extinct species, it also triggered a sharp rise in human-elephant conflict, especially in Mahasamund, where agricultural expansion and denser human settlements brought elephants into frequent contact with communities. Incidents of crop raiding, property damage, and even fatalities due to electrocution began to increase when elephants began to adapt to farmlands to forage. Unlike the relatively tolerant tribal communities of Balodabazar, many residents of Mahasamund were unprepared for these encounters, resulting in growing fear, retaliatory actions, and pressure on local authorities. This escalating conflict in both districts, and the growing need to promote a sense of coexistence and safety for both humans and the herd of elephants colonising the areas, prompted Wildlife SOS, along with the Chhattisgarh Forest Department, to intervene. An in-depth study of elephant movement, behaviour, and conflict patterns in the region was launched, laying the groundwork for science-based strategies for long-term coexistence. The findings that we discuss in this article have been documented under “Technical Report Radio Collaring & Early Warning Alert System of Human-Elephant Conflict Mitigation Project in Chhattisgarh State 2018-2021”.

- As elephants adapt to human-dominated landscapes, conflict over crops and space becomes inevitable. [Photo © Chhattisgarh Forest Department]

Mapping the Migration Routes

Through extensive field surveys, interviews with villagers, and data collection from local forest range offices, the team, which comprised field biologists, elephant trackers, veterinary staff and forest rangers, pieced together the movement routes taken up by elephants. Early sightings date back to 2014-15, when villagers in Balodabazar reported two or three tuskers, followed by sightings of the entire herd of about 14 elephants that expanded to 17 by the end of 2015. But where were they coming in from? Most likely, the adjacent forests of Odisha were home to roughly 1,976 elephants according to India’s 2017 synchronised population estimate.

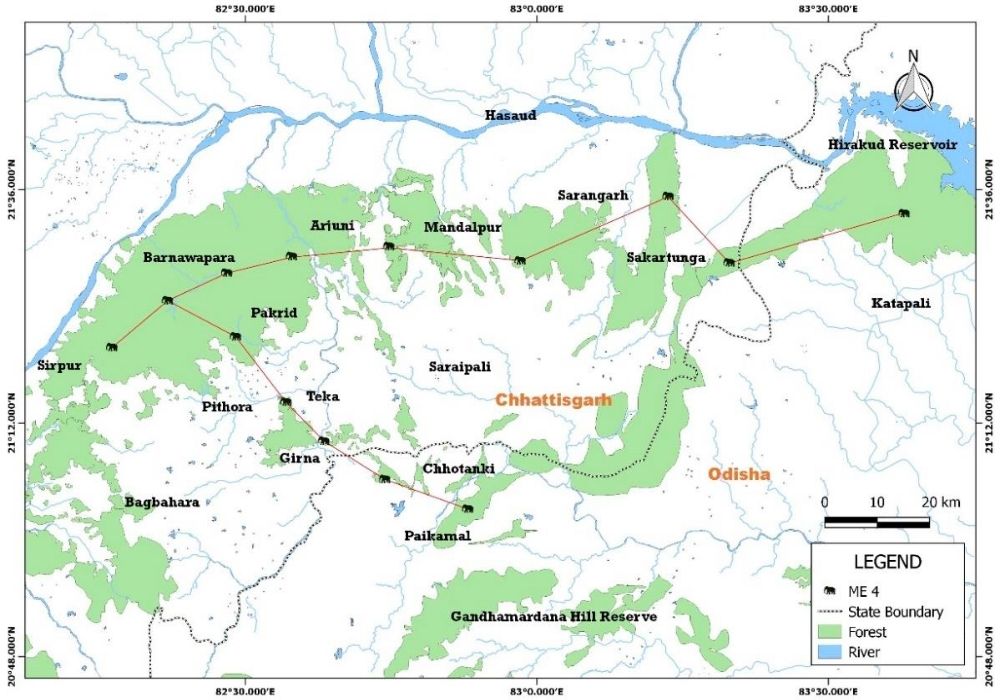

- Map showing the elephants’ migration from Odisha to our study areas. [Photo © Chhattisgarh Forest Department & Wildlife SOS]

Our research identified two potential main migration routes from the Narsinghnath forests near the Hirakud dam in Odisha into Chhattisgarh:

- From Narsinghnath to Raigarh, from where they crossed Gomarda, Saraipali, and Barnavapara sanctuary, to finally reach Mahasamund.

- They entered Girna in the Pithora range of the Mahasamund region through the Bundeli circle near the Odisha border.

Finding these routes reaffirms elephants’ remarkable ability to navigate fragmented landscapes with determination to search for apt habitats. However, their migration also resulted in them entering agricultural fields to feed on nutritious and non-toxic foliage, as the areas studied also had an overall scarcity of grass.

Understanding Elephant Herds and Movements

To begin understanding herd distribution and its movement in the locations under study, the Wildlife SOS team focused their efforts on radio-collaring the matriarch of a 17-member herd in 2017. The efforts were finally successful when the matriarch was tranquilised and a GPS (Global Positioning System) radio collar was carefully fitted on her neck. Then referred to as Chanda (ME4), she was later named Van Devi. This milestone began our urgent study of understanding her herd’s movement and behaviour, and also laid the foundation for conflict mitigation. By 2019, this very herd had grown to 22 elephants with the birth of five calves, reaffirming the importance of long-term tracking and coexistence strategies in Chhattisgarh.

- Our team radio-collared Chanda, who we know as Van Devi, to monitor the mighty matriarch’s movements, understand the location of her herd in Chhattisgarh, and alert the locals on time of their proximity. [Photo © Wildlife SOS]

Along with Chanda’s herd, Wildlife SOS and the Chhattisgarh Forest Department also identified the presence of other herds that had moved into the region, including:

- Pithora herd (6 elephants): Entered Mahasamund in 2018, with some splitting and moving between Odisha and Chhattisgarh, causing occasional crop damage and human-wildlife conflict.

- Rohansi (Tony) herd (19 elephants): Migrated into Balodabazar in 2019 from Odisha, dispersing across several forest ranges.

- Ram and Balaram: Two adult male tuskers who entered in 2019, traversed multiple forest divisions, and eventually reached Madhya Pradesh, covering over 850 kilometres in three months.

- Gariyabandh herd (25-30 elephants): Entered from Odisha in 2020, currently active in Gariyabandh and Dhamtari divisions.

- Guided by memory and instinct, elephant herds journey across states in search of safer, resource-rich habitats. [Photo © Chhattisgarh Forest Department]

Population and Distribution

GPS and VHF (Very High Frequency) data revealed that in Baladobazar, the Van Devi herd roamed over a range of 4,300 km sq. in 2019 and 1,182 km sq. in 2020, a large difference from movements that were recorded at approximately 790 km sq. from 2015 to 2017. Varying expanse suggests that newly migrating elephants were in the process of establishing their range, and some were dispersing from there as well. Tribal communities residing in scattered villages here, which are closer to the forests, were understood to be more tolerant towards wildlife entering their spaces. These areas also remain mostly forested, with little progress on infrastructural development. In contrast, Mahasamund had quickly become a conflict hotspot as the human population here was greater, and with agricultural development, encounters with elephants began to rise.

Tracking the Herds and Mitigating Conflict

Female elephants are typically responsible for crop-raiding, especially when they are accompanied by calves. However, they tend to avoid direct confrontation with humans, often out of fear and a need to protect their young. In contrast, male elephants, being bolder and more solitary, are more likely to engage in aggressive behaviour and are usually the ones involved in attacks on people. Such incidents can lead to retaliation by communities, contributing significantly to elephant mortality. One of the major reasons behind elephant mortality included electrocution from electric fences that were installed as safeguards against elephant intrusion, and this raised grave concerns. To prevent such incidents, measures like raising low-lying power lines and standardising solar fence systems were recommended. Farmers were also encouraged to avoid using loosely sprawled wires and adopt safer field-illumination practices.

- Drone shots capture the majestic movement of a wild elephant herd through the forests and fields of Mahasamund, Chhattisgarh. [Photo © Chhattisgarh Forest Department]

The persistent human-elephant conflict in the region was what first prompted the need for scientific intervention. GPS radio-collaring played a crucial part. This enabled real-time tracking of elephant movements across highly fragmented, human-dominated landscapes. This data was used to activate Early Warning Systems (EWS), through which forest officials and local community volunteers in vulnerable villages were instantly notified via WhatsApp groups of the elephants’ location. This advance warning gave communities critical time to take precautionary measures, significantly reducing the risk of sudden encounters and conflict.

As expected, the GPS collar on Van Devi worked for two years till its battery lasted. However, tracking the herd was still possible through the VHF system on the collar. A year later, Van Devi’s collar came off altogether, which halted our ability to know the exact location of the herd. The Van Devi (Chanda) herd, which once was a cornerstone of our movement study, has moved out of Chhattisgarh and was last sighted in Maharashtra.

The Way Ahead

Chhattisgarh has always been a migratory route for elephants travelling to neighbouring states. Today, only two herds remain in central Chhattisgarh — the Rohansi herd, currently active in the Balodabazar division, and the Gariyabandh herd, which remains within the Gariyabandh division. Wildlife SOS, along with the help of the locals and the forest department, continue to track these herds through the age-old method of ground monitoring with trackers. In addition to these herds, a few solitary males also roam the landscape. Our focus remains on preventing conflict in Balodabazar and Gariyabandh by strengthening field-based observations and community engagement.

Elephant migration into Chhattisgarh is a reflection of both anthropogenic and dynamic ecological factors in central India. When knowledge and awareness were shared among villagers unfamiliar with elephants and their behaviour, the situations of conflict could be handled better. Wildlife SOS, along with the state forest departments, keeps expanding its protection efforts using technology, on-ground tracking of elephants and community involvement. Policies and procedures meant to lessen human-elephant conflict and promote lasting coexistence are informed by insights from our focused studies.

Read more about our efforts to mitigate human-elephant conflict here.

Feature image: Wildlife SOS