Captivity (noun)

Oxford Dictionary defines captivity as “the state of being kept as a prisoner or in a space that you cannot escape from.”

All throughout history, through battles and through wars, through pens and swords — mankind has fought to escape from one form of captivity or another. Some of these forms came dressed in oppressive rules, and some came in the form of slavery and discriminatory laws. Humans, who continue to be divided through the various societal constructs of colour, caste, religion, language, beliefs — have once, in history, stood united against all states of captivity.

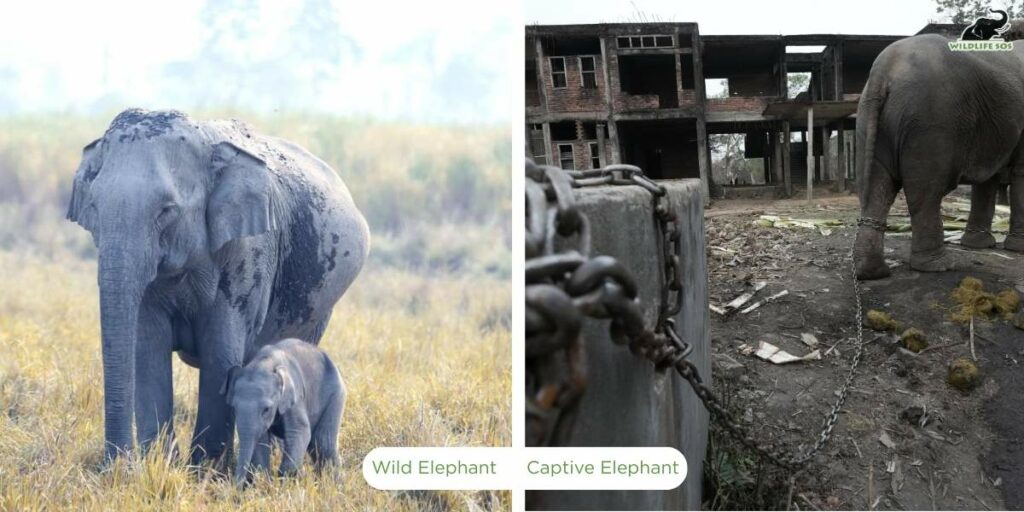

In his book The Life of Reason (1905) philosopher George Santayana wrote, “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” And condemned we are, after subjecting cruelty on our nation’s once flourishing wildlife. Nowhere is this gruesome reality more vivid than in the lives of India’s elephants, who are, ironically, revered in temples and are subjects of devotion. Yet, they are poached from the wild and are kept shackled, starved, and abused. Unlike elephants that are free and roam the ancient forests of the Western Ghats or the floodplains of the Brahmaputra with their matriarchal herds, there are many that stand in the blistering heat of a highway-side temple, swaying in trauma, far from any herd, far from any forest, and farther still from freedom.

Ripping animals apart from their ecosystems impacts their physical and psychological well-being. If we take a moment to closely observe them, the bare truth of what captive elephants face is painfully etched into their blinded eyes, worn-out feet, torn ears, spine deformities, and a peculiar gait.

Captivity Vs Domestication

It’s impossible to miss the colossal frame of an elephant lumbering down a busy street. The sheer size alone demands our attention. Adorned in bright paints and decorative cloth, the elephant walks with a reluctant gait, head bobbing rhythmically, which many misinterpret as an amusing act. At its side, a much smaller human — often barefoot — walks by as the elephant’s owner, carrying a long stick. And somehow, we marvel at the mismatched sight.

Imagine taming such a giant, we think. But this thought that the elephant is “tamed” or “domesticated”, is dangerously misleading even as it crosses our mind. The term domesticated refers to animals that have undergone generations and generations of selective breeding so as to make them more compatible with humans. Like in the cases of dogs, cats, poultry, or cattle. These animals have genetically altered over years, so every generation inherits traits like docility, dependency, and human sociability.

Elephants do not fall into this category.

Despite being used by humans for thousands of years in war zones, logging timber, religious processions, tourism: elephants have never been domesticated. They are wild animals kept in captivity. Each one is either captured from the wild in their infant hood or is born to parents who were captive. Their instincts, emotions, and intelligence remain those of untameable, wild beings.

Wildlife SOS has rescued and rehabilitated many elephants from traumatic situations under captivity, and the conditions we found them in are heart-wrenching. What better way to understand the difference between wild and captive elephants than by comparing the two visually, side-by-side. After all, seeing is believing.

- Eyes

In the wild:

Bright, alert, and expressive, elephant eyes in the wild encase deep emotional intelligence and social curiosity. They’re constantly scanning their surroundings, learning from the environment, responding to family members’ movements, or watching over calves with gentle attentiveness. Their gaze holds memory, instinct, and wisdom of the forest.

Left: Wildlife SOS/Mradul Pathak; right: Wildlife SOS/Vineet Singh

In captivity:

Dull, lifeless, and often damaged, captive elephants frequently suffer from partial or complete blindness. This is not always a tragic consequence of neglect, but occasionally a deliberate act. We have come across cases where elephants are purposefully blinded by their owners using cruel methods to make them more docile and easier to control. Malnutrition also plays a silent role in causing degenerative eye conditions that lead to eventual blindness. The vacant stare of a captive elephant speaks not just of physical decay, but of a deeper psychological trauma; the light behind the eyes extinguished by years of suffering.

One such elephant is in our care is Manu, a blind elephant, who embodies this tragic reality. Forced to beg on city streets and paraded through ceremonies, he endured years of neglect. One of his eyes was deliberately blinded with a sharp object, while the other deteriorated over time due to malnutrition, age, and prolonged suffering. By the time he collapsed from exhaustion and infection, Manu’s eyes had long been robbed of their light, leaving behind only the shadows of his trauma.

- Ears

In the wild:

Large, intact, and frequently flapped, elephant ears are interestingly a part of their complex communication. While an elephant’s ears help alleviate excess heat when they flap it, they can also express their mood by spreading wide in alertness, or relaxed when calm.

Left: Wildlife SOS/Mradul Pathak; right: Wildlife SOS/Mradul Pathak

In captivity:

Torn, scarred, and mutilated by repeated jabs from bullhooks or nails during phajaan, training, and while taking control of the large mammal. Piercings for decorative ornaments during temple processions also cause permanent damage.

Chanchal, who is under our care, was used during wedding processions, and she endured repeated jabs with the pointed end of the bullhook, which painfully tore and damaged the edges of her ears. She had spent her years bearing a heavy howdah (saddle) on her back, which weakened her limbs. A persistent ear infection and a slowly developing cataract haunt Chanchal, proving the ill effects of abusive captivity.

- Tail

In the wild:

The tail is a functional appendage, often used like a fly swatter for the backside of their body or for tactile bonding as mothers brush their calves gently with it. Elephants also tend to touch each other’s tails in single-file movements to stay connected. The tail hair can also be studied to reveal the elephant’s diet and his surrounding environment.

Left: Canva; right: Wildlife SOS/Mradul Pathak

In captivity:

Frequently injured or with abscesses, the tails of elephants in captivity are often used to tie them down and stop their movement. The ropes used to ride or keep them captive also cut through their flesh, leading to infections left untreated. The absence or shortening of the tail is also often a sign of a violent or negligent past. Many pluck elephant tail hair, believing it to be ‘auspicious’ or as a talisman, or for medicinal use to help alleviate ailments like headaches and arthritis. This cruel practice not only causes immense pain but can also lead to open wounds and long-term injury to the sensitive tail base.

Raju’s tail had been cruelly plucked for ‘good luck’ charms, leaving raw, painful wounds. When he was rescued, veterinarians noted that his injuries required urgent care. The tail had been tied to an iron pole in captivity, preventing him from using it naturally. While he was receiving treatment, Raju would tend to repeatedly rub his tail against trees or walls, which slowed its healing. Rest, careful monitoring, and regular dressings were what led to Raju’s tail recovery, emphasising how important care and medical attention is for suffering elephants.

- Foot pad

In the wild:

Thick, healthy, and sensitive, foot pads help the fantastically massive elephants spend most of their time on their feet! Walking, foraging, or simply standing for hours indicate they need strong foot support. Hence, their feet are equipped with cushioned pads that evenly distribute their massive body weight, reducing pressure on the bones and joints. Hidden within these pads are predigits (enlarged, false toes) that act like internal shock absorbers, transferring weight efficiently from the sole to the limb. Moreover, they serve as sensitive instruments capable of picking up low-frequency ground vibrations. This remarkable ability allows elephants to detect distant movements, whether it’s the approach of another herd or an oncoming threat, long before it’s visible.

Left: Wildlife SOS/Vineet Singh; right: Wildlife SOS/Vineet Singh

In captivity:

Cracked, infected, and calloused, the foot pads of captive elephants repetitively land on hard concrete or hot tarmac and face these consequences. Their foot pads are not designed for unnatural surfaces. Abscesses, arthritis, and footrot are consequences that are painful, often leading to life-threatening complications. Moreover, overgrown, split, or cracked nails and damaged cuticles are common in captivity, making each step excruciating for the pachyderm, exposing the feet to infection as well.

Most of the elephants that come under Wildlife SOS for care and rehabilitation arrive with severely damaged foot pads. Elephants like Rhea, Mia, Nina and Chanchal are among the elephants who were forced to walk on harsh surfaces that led to thinning and wearing out of their foot pads. Under Wildlife SOS’s professional medical care, they are receiving regular foot care and treatment to provide them with relief and comfort.

- Physical Deformities

In the wild:

Elephants in the wild grow naturally, with strong muscle tone and appropriate body mass supported by free movement and a high-fibre forest diet. Their spines remain curved and their legs straight, with healthy foot pads that aid them for long-distance walking.

Left: Wildlife SOS/Akash Dolas; right: Wildlife SOS/Vineet Singh

In captivity:

Sunken temples and protruding bones, along with spinal deformities and abnormal gaits, are commonly observed in elephants kept in inhumane captivity. Their large size leads to a widespread misbelief that elephants can handle weight on their backs. This is not true. Carrying people or goods on a heavy saddle on their backs damages their vertebrae. Moreover, malnutrition stunts their growth, and prolonged tethering leads to atrophied muscles and unnatural joint angles.

Vayu, a 52-year-old tusker, once used in the logging trade of Northeast India, bears the weight of this truth. A devastating fall fractured his forelimb, and without proper medical care, the bone healed poorly, leaving him permanently disabled. As his crippled leg strained the rest of his body, arthritis, ankylosis, and severe foot problems set in. Currently, with focused attention, mighty affection and carefully prescribed treatments by our team, Vayu has begun a journey towards healing under long-term care. To protect elephants like Vayu, say No to elephant rides and spread awareness on ethical tourism through our Refuse to Ride campaign.

- Inherent Instincts, Behaviour & Memories

In the wild:

Elephants are deeply intelligent beings with exceptional memories. Calves learn migratory paths, locations of waterholes, seasonal fruiting trees, and danger zones from elders — usually passed down through the matriarch of the herd that functions like a joint family.

Left: Wildlife SOS/ Hemanta Bijoy Chakma; right Wildlife SOS/Mradul Pathak

In captivity:

Captive elephants that were taken from their herd in the wild as young calves never learnt the survival skills of their species. The knowledge of their land, the feeling of soil under their feet, or the distinct calls made by members of a protective herd — all are lost forever. Instead, they are tied up and taught to obey commands through fear and pain.

For rescued elephants, Wildlife SOS tries to bring back pieces of that lost life. One way to successfully revive their natural instincts and keep them physically and mentally healthy is by creating attractive food-based enrichments. Enrichments filled with fresh fodder by caregivers allows them to discover and practice their inherent skills to solve challenges. Another way to provide them with the comfort they need is by maintaining the fields they walk on. Rescued from walking on harsh surfaces, the softness of natural ground that they are deprived of all their lives now provides great relief to elephants suffering from injuries or medical issues in their limbs.

- Socialisation

In the wild:

Elephants are renowned for their strong family bonds and rich social lives. They can remember other individuals and places for many years, forming lasting connections. The relationships in a herd extend from the core mother-offspring bond to families, clans, and even interactions with strangers.

Elephants live in tight-knit matriarchal herds. Their group lives as a society that merges or splits naturally while moving through the environment, the strength, and structure of which can shift over time, influenced by age, experience, and changing group dynamics. Females remain with their mothers for life. Adult males are known to break away from the herd and live independently, but they engage socially during musth or mating seasons.

Left: Wildlife SOS/Hemanta Bijoy Chakma; right: Wildlife SOS/Mradul Pathak

In captivity:

In India, social isolation is a grim reality for many captive elephants. Some spend their entire lives alone, deprived of companionship, crammed in small dark rooms with no space for any movement. For such intelligent, herd-loving animals, this form of captivity is among the cruellest — the emotional equivalent of a human being sentenced to lifelong solitary confinement.

Maya and Phoolkali, rescued from a circus and a life of begging respectively, quickly became an inseparable duo at Wildlife SOS, sharing walks, play, and comfort. Nine years later, Emma was rescued, and it was astonishing to see how Phoolkali gently guided her into the group of two, converting it into a warm, trusting trio. By being able to form a bond of companionship, the three elephants have rediscovered their natural social behaviour based on trust, proving the point that healing from trauma is as much social and emotional as it is physical.

- Diet

In the wild:

Wild elephants spend between 16 and 18 hours a day foraging and can consume up to 5% -10% of their body weight in fresh fodder. While they generally feed on what is readily available, they often show selectiveness, choosing specific parts of a plant. Their appetite can make room for a range of grasses to various parts of trees and plants, including leaves, branches, roots, seedlings, vines, flowers, stems, and fruits.

Left: Canva; right: Wildlife SOS/Vineet Singh

In captivity:

Stale sugarcane, rice, roti, or packaged snacks are unhealthy items that cannot support the nourishment they need. Poor diets cause digestive problems, obesity, and nutritional deficiencies. Combined with lack of movement, this severely impacts their mental as well as physical health.

Laxmi, once used as a ‘begging’ elephant in Maharashtra, is a stark example of how captivity distorts even an elephant’s natural diet. Instead of fresh foliage, she was fed oily fried foods and sweets from the streets, which left her overweight and suffering from osteoarthritis. In contrast stood Lakshmi, cruelly known as “India’s skinniest elephant”, whose bent knees, protruding spine, and sunken temples bore witness to years of starvation and neglect.

Their recoveries began with food. For Laxmi, the priority was reducing the strain on her limbs through a carefully balanced diet, replacing oily street food with fresh fodder, fruits, and fibre-rich supplements. For Lakshmi, the focus was gradual nourishment, ensuring her frail body could steadily rebuild lost muscle and fat without overwhelming her weakened system.

Beyond Chains: Extending Help to the Wild Ones

At Wildlife SOS, we understand that elephants need protection not just from captivity, but also from the growing dangers that threaten them in the wild. Rapid urbanisation, deforestation, and encroachment into traditional elephant corridors are forcing these gentle giants into fragmented habitats, where the risks of injury, conflict, and death escalate each day. Railway line collisions, electric fence electrocutions, snares, crop-related retaliation — wild elephants are increasingly caught in the crossfire of survival.

That’s why our commitment extends beyond the walls of our sanctuaries. Through our Haathi Sewa mobile veterinary unit, Wildlife SOS provides critical on-site medical care to wild elephants injured or distressed across states. Our team also works closely with forest departments to conduct field rescues, deliver emergency treatment, and support long-term conflict mitigation as well as rehabilitation.

Of Memory and Mercy

Perhaps the most vanquished beings of all are those who cannot speak of their memories, like the captive elephants who never got the chance to roam free. Some remember the feel of forest trails underfoot before chains replaced them. Others, taken as calves or born in captivity, have never known the wild world at all. The difference between a wild and a captive elephant is more than just habitat. It is the difference between a life lived and a life endured. Between choice and control. Between instinct and obedience. Between thriving and merely surviving.

If this truth stirs something within you, let it lead to action. At Wildlife SOS, we are working every day to rewrite the fate of India’s captive elephants. But we cannot do it alone. Your support fuels this mission of mercy. You can donate for and sponsor the care of an elephant If you ever see an elephant distressed being chained, injured, being beaten or forced to beg — don’t look away. Report it immediately to Wildlife SOS at our 24×7 Elephant Helpline: 91-9971699727 or email us at info@wildlifesos.org.

Your voice could be the first step in setting them free.

Feature image: Mradul Pathak/ Wildlife SOS